I admit it, Nagasaki was never at the top of my list of Japanese destinations to visit, but once there, I discovered a truly unique city, with a strong international influence despite the small number of foreign tourists, and with incredibly kind people eager to chat.

Undoubtedly, the first thing we associate with Nagasaki is Hiroshima and that terrible fate that linked the two cities: the dropping of the two atomic bombs eighty years ago, at the end of World War II.

I have visited both cities, but I still haven’t been able to write about Hiroshima, because the weight of that terrible day feels like a punch to the stomach every time I sit down to write—it’s always there, an invisible weight that permeates the entire city. Nagasaki, however, has a different atmosphere. Despite the more than 80,000 victims of that day, it welcomes you by telling you that its history goes far beyond that tragic moment.

A port city, a crossroads of trade and markets, the only port to remain partially open during Sakoku, Japan’s isolationist period. In addition to shrines and temples—including Chinese ones—you’ll also find churches here. Towering modern buildings stand beside Western-style villas, traditional Japanese houses, and roofs in Chinese style. Even the food is a mix of foreign influences, especially Chinese and Portuguese.

Since the 1500s, Nagasaki has been a hub of trade between Japan and the West, particularly with the Portuguese, who also brought Jesuit missionaries such as Francis Xavier. They introduced Christianity to Japan, which is why you’ll find several Christian churches not only in Nagasaki city but throughout the prefecture. Initially tolerated, Christianity was later deemed dangerous, and persecution began. The peak was on February 5, 1597, when 26 Christians (six Western bishops and 20 Japanese converts) were executed in Nagasaki by being pierced with spears. Near the station, you’ll find a monument dedicated to the 26 martyrs, and religious tourism in this area has been steadily growing.

In the 1600s, during Japan’s isolationist period, Nagasaki was the only port allowed to trade with the outside world—though under strict surveillance and very rigid conditions imposed on the foreigners who lived here. In the 1800s, many merchants and businessmen, such as Thomas Blake Glover, built their villas here to manage trade with the West.

I loved strolling through Nagasaki’s streets. It cannot be described as beautiful or elegant like, for instance, Kanazawa, but it has a certain charm, perhaps a bit desolate, that makes it unique. Despite having several sights worth visiting, I never found it crowded. Tourism here is mostly domestic, with very few foreign visitors—both Westerners and Asians—while other Kyushu cities like Fukuoka are literally invaded.

What to See in Nagasaki

To visit Nagasaki, a couple of days is enough, which can easily be included in a trip to Kyushu island. I invite you to request a consultation or my travel design service to help you best integrate it into your Japan itinerary. The city is easy to get around by tram and bus, but it’s also very pleasant to explore on foot, despite the constant ups and downs of this port town surrounded by hills. A car is not necessary in the city, though it might be useful if you plan to visit nearby Unzen or the Shimabara Peninsula.

In any case, there is no shortage of things to see in Nagasaki, and by visiting, you’ll be able to walk through its history, recognizing the different eras, tragedies, and foreign influences that shaped the city. Below I list what to see in Nagasaki in geographical order, from north to south, so that you can easily replicate the itinerary over two days.

Nagasaki Peace Museum and Peace Park

Nagasaki was not supposed to be hit by the atomic bomb. The designated target was Kokura, in northern Kyushu, since it was the main shipbuilding port for war vessels. But bad weather made the drop impossible, so the mission turned to Nagasaki, where Mitsubishi’s shipyards were located.

Due to Nagasaki’s geography, the effects of the atomic bomb dropped on August 9, 1945, were “limited” to the northern part of the city, where today you’ll find the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and Peace Park. Both are smaller in scale compared to Hiroshima’s, and in some ways different.

The museum is definitely smaller and less harrowing than Hiroshima’s, but the chills of horror at what mankind was capable of will grip you here as well. Leaving the museum and heading towards the park, you encounter a huge black monolith marking the exact hypocenter where the “Fat Boy” bomb exploded on August 9, 1945.

Peace Park is a rectangular area that once held Nagasaki’s prison, remnants of which can still be seen. Today it is a green space filled with art and water features, culminating in the great Peace Statue. Its right hand points to the sky, symbolizing the threat of nuclear weapons; the left hand stretches outward to represent tranquility and world peace; and its closed eyes express a prayer for the souls of all war victims. The impact is truly overwhelming.

Hours: Daily, 10:00–17:30

Admission: 200 JPY

Dejima

Dejima was once a small fan-shaped island in the heart of Nagasaki. Today it is fully incorporated into the urban landscape, since the surrounding canals were filled in. But stepping inside still feels like a leap back in time, when Dutch merchants of the East India Company were confined to this tiny strip of land during Japan’s isolationist period.

It was a miniature Holland, with houses, shops, and warehouses, from where the only foreign trade permitted at the time flowed in and out. The buildings have been faithfully reconstructed, and Dejima is now an open-air museum, complete with free guided tours in English (advance reservation required, usually on site).

Even if, like me, you don’t manage to join a guided tour, each building contains explanatory panels in English, along with videos and multimedia elements to deepen your understanding of this unique and historically important corner of Japan. At the time of my visit, a couple of buildings were still closed to the public for restoration and research, but the accessible area was already quite extensive and even includes a café-restaurant serving dishes that are a true blend of Japanese and European flavors.

Hours: 8:00–21:00, daily

Admission: 520 JPY

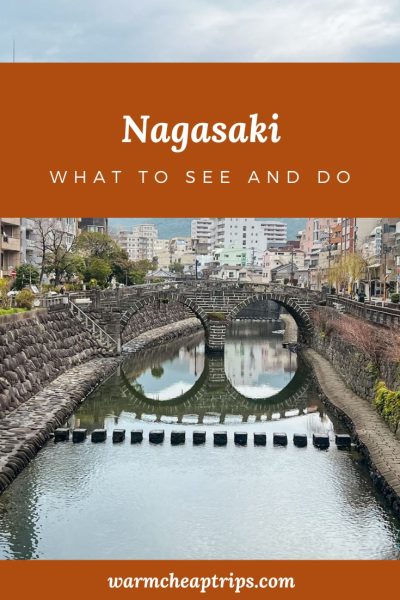

Megane Bashi and Chinatown

Speaking of foreign influences, China also had extensive trade ties with Nagasaki, so much so that Japan’s oldest Chinatown is found here. Although much smaller and quieter today than those of Yokohama or Kobe, you can still find many Chinese-style buildings integrated into the cityscape, adding to Nagasaki’s eclectic charm. Several Chinese temples are also nearby in tera-machi, such as Kofukuji and Sofukuji with its iconic red gate.

Walking along these stone-paved streets, between little shops and tangles of overhead power lines, you can feel the living energy of Nagasaki, the history of the people who lived here, and the coexistence of ideas and worlds that found such an unusual home in a closed, homogeneous country like Japan.

This route also leads you to the highly photogenic Megane-Bashi Bridge, built in stone in 1634 by a Chinese monk who later became the head priest of Kofukuji Temple. Its name (“megane” = glasses) comes from the way its double-arched reflection in the canal resembles a pair of eyeglasses.

Mount Inasa Observatory

The perfect way to end a day in the city is with the view from Mount Inasa. This 300-meter hill offers a breathtaking panorama of Nagasaki. When I say breathtaking, I mean it—it is considered one of the three best night views in the world!

I recommend taking the ropeway up (720 JPY one-way) and then walking back down through the park below, where you can catch a bus back to the city center. Just be mindful of the timetable, as buses from Inasayama Park are limited, making the ropeway the safest option for returning.

Glover Street: Glover Garden and Oura Cathedral

In the southern part of Nagasaki, Western—especially Portuguese—influence is unmistakable. This hilly district is dotted with Western-style brick buildings, cobblestone streets, and villas with gardens. I loved this area, despite the uphill climbs, also because it often opens up to lovely views of the port and Nagasaki Bay. The best viewpoint, for example, is within the Glover Garden, a beautiful Western-style garden named after the villa of Thomas Blake Glover located inside. Alongside it, you’ll also find several former merchant residences, making for a delightful stroll through this European corner of Japan. At 11:00, 13:00, and 15:00, you can also join free guided tours in English.

The garden is located along Glover Street, the main road climbing the hill, lined with souvenir shops and castella, Nagasaki’s sponge cake of Spanish origin (Castilla cake). You’ll also find Oura Cathedral, built in 1864 and dedicated to the city’s 26 martyrs, with an adjacent museum.

Glover Garden

Hours: 8:00–18:00, daily

Admission: 620 JPY

Oura Cathedral

Hours: 8:30–18:00, daily

Admission: 1,000 JPY

Hashima Island (Gunkanjima)

I admit, the thing I most wanted to see on my trip to Nagasaki was this uninhabited island shaped like a battleship, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its role in Japan’s industrial revolution. It can only be visited on guided tours, and only a small portion of the island is accessible. Tours are canceled in case of heavy rain or rough seas. Sometimes boats can approach the island but cannot dock due to strong currents. You need a bit of luck… and my good fortune held out, allowing me to set foot on this fascinating island.

This concrete island deserves an article of its own—and perhaps I’ll write one eventually. Hashima is one of the many islands in Nagasaki Bay used for coal mining in the 20th century. Over 5,000 people once lived on this tiny island in Japan’s first reinforced-concrete buildings, built to withstand typhoons and waves. Miners risked their lives daily in deep underground tunnels, while their families lived in tall brutalist apartment blocks. Despite the harshness, there was a strong sense of community, and some former residents, now working as guides, recall it almost nostalgically.

As often happens, Japan’s narrative focuses on the island’s innovative aspects at the time, the social bonds it fostered, and the economic opportunities it represented. But the reality is undeniable: living and working conditions were extremely tough, and it is believed that Chinese and Korean prisoners were also exploited here.

Mining operations ceased in 1974, and Hashima was abandoned. Over the years, typhoons caused structural collapses, enhancing its aura as a ghost island. In 2009, a dock was built and a small section in the island’s southern part—the area furthest from the buildings—was opened to guided tours. Tours are conducted in Japanese but are very accessible to foreigners thanks to a comprehensive English guide booklet provided at the start of the tour—if you book with Gunkanjima Concierge. I strongly recommend their tour, as the ticket also includes entry to the Gunkanjima Digital Museum (with explanations and subtitles in English). It’s an excellent, immersive experience, with augmented reality showing parts of Hashima that cannot be visited, like the residential blocks.

The tour lasts about three hours, including around 45 minutes on the island (when possible), and plenty of time navigating around it so you can admire its ship-like silhouette. Reservations are required, and spots fill up quickly. In case of cancellation, you’re usually notified the same morning. If boats go out but cannot dock, the 310 JPY landing fee is refunded. Bring seasickness medication if needed—the staff will also offer candies for the open sea crossing. Umbrellas are not allowed on the island, so bring a raincoat instead.

Hours: 8:30–18:00, daily

Admission: 5.200 JPY

Where to Stay in Nagasaki

Visiting Nagasaki for work gave me the chance to check out several hotels and stay in two different ones. The station area is very convenient for transportation, with many dining options nearby. But I especially loved the Glover Street area—perhaps because the cobblestone streets and European vibes reminded me of home… though finding dinner was trickier here, since most cafés close around 6 pm. A short walk toward the sea, around Dejima Wharf, solves the problem with good restaurants.

In this area, I stayed at the hotel Monterey Nagasaki, housed in a Western-style historic building, complete with a charming retro elevator and tiled floors—something rare in Japan. It’s just a short walk to both bus and tram stops, and Glover Street and Chinatown are easily reached on foot.

In the station area, I stayed at the hotel New Nagasaki, a very large hotel with a bus terminal right in front. Buses depart here for all directions, making it incredibly convenient.

Walking through the streets of Nagasaki means embarking on a journey through its history. A place that invites reflection, but also wonder. For this reason, I strongly recommend including it in your Kyushu itinerary!

Planning a trip to Kyushu? Here are more articles about this region!